It didn't take long at all until I spotted the first wigeon of the day.

Though small numbers of wigeon do breed in the UK (in Scotland and the North of England), all the wigeon around here are winter visitors from Russia, Scandinavia and Iceland1. The key identifying feature of wigeon are there bright yellow forehead, though this is only the case in males- females of most of our duck species look very similar.

Also on the reserve were a flock of brent geese- whilst I have seen these birds at the reserve before, yesterday's visit was the closest I've seen them to the footpath on top of the sea wall.

These brent geese come from a long way North, the Taymyr peninsula on the Arctic coast of Siberia. They fly some 5000 kilometres to reach us, cutting over Finland and going around the southern shore of the Baltic Sea on their journey2. They spend the winter feeding on eelgrass and on crops in nearby fields3. There are several subspecies of brent geese- these are dark-bellied. Scientists are divided upon whether these subspecies are genetically different enough to be identified as separate species altogether- at the the moment they remain one species.

One further migratory bird I spotted was this greenshank.

I'm lucky to live in one of the few parts of the UK where you can see greenshank in the winter. Many pass through the east coast and they can be seen in Cornwall and Devon but the only place further west than that in England is around the solent4. Indeed, we are lucky to have greenshank this far North at all during winter as the vast majority spend their winters in Africa, the Indian subcontinent and Australasia.

So why do so many migratory birds spend winter at Lymington-Keyhaven? The reserve contains both a salt marsh and mudflats which are home to the invertebrates that these birds need to eat in vast numbers to survive5. There are also large creeks between the salt marsh which are perfect nursery areas for fish, again providing food for many of these species. The salt marsh also sits behind the sea wall which means these birds have their ideal coastal habitat yet are sheltered from the worst of the winter weather.

Of course, I didn't just see migrants, I also saw plenty of resident birds. The highlight of these was the kingfisher which seemed to follow me around the reserve.

Kingfishers are highly territorial birds- this it because they have to eat around 60% of their own body weight every day and so have to have control of a suitable stretch of river 6. They will fight off intruders, grabbing their beak and trying to hold it under the water. Territories are somewhere between half a mile and two miles long so it's likely this bird is the king of the Lymington-Keyhaven.

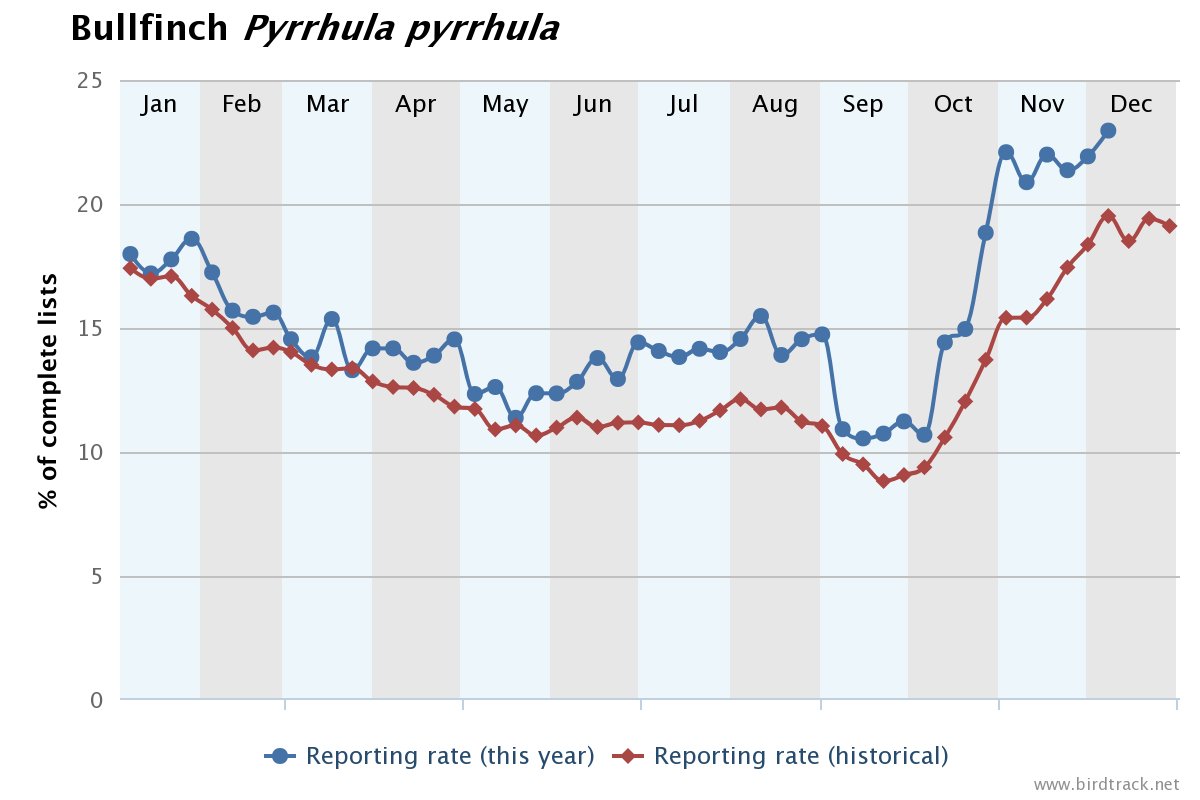

To conclude today I just wanted to refer back to a post from a few weeks ago. I speculated that 2017 had been a good year for bullfinch numbers. Well the BTO's BirdTrack survey has found hard data to support my own observations. This graph shows just how high the number of bullfinch sightings this year has been compared to usual 7.

It's always nice to have my own observations made official! That's all for today but I'll hopefully be out and about lots over the festive season so there will be more soon!

1: RSPB- Wigeon

4: RSPB: Greenshank5: RSPB New Forest Local Group: Lymington-Keyhaven Nature Reserve

6: Fry, H. Fry, K and Harris, A (1999) Kingfishers, Bee-eaters and Rollers. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 219-221

7: Twitter: BTO

Thanks for your blog. Good to see a variety of bird life out there.

ReplyDelete